Tis but thy name that is my enemy;

Thou art thyself, though not a Montague.

What’s Montague? It is nor hand, nor foot,

Nor arm, nor face, nor any other part

Belonging to a man. O, be some other name!

What’s in a name? That which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet;

So Romeo would, were he not Romeo call’d,

Retain that dear perfection which he owes

Without that title. Romeo, doff thy name;

And for thy name, which is no part of thee,

Take all myself.

William Shakespeare – Romeo and Juliet

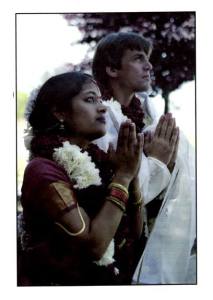

My Mom likes to tell the story about how, on the first day of Montessori preschool, that I walked up to the teacher and proudly said, “My name is Aparna Sreenivasan, and you spell that: A P A R N A S R E E N I V A S A N.” Apparently the teacher told me how smart I was, and then I turned to my Mom and said, “Mom’s don’t go to this school, see you later.” As I bounced into my new world of school, she burst into tears.

I have always liked my name, Aparna, because in West Virginia, and Pennsylvania, and even in California, it was unique. I also like my name because it has an ancient meaning. My first name, Aparna, is of Sanskrit origin, and has many meanings, “she is without debts,” is one of them, and no, it doesn’t mean that I have lots of money. Indeed it stems from Aparna’s other name, Parvati the goddess, who is infamously married to Lord Shiva, the destroyer, and the grumpiest of the three major Gods in the Hindu religion. Parvati has many other names: Gauri (her name as the mother of Ganesha), Kali (the warrior princess), and Durga (another warrior princess). But let’s get back to Aparna:

Aparna means without debts because she repays all of the devotion she is given by giving boons (gifts) to her devotees. She is also known as the “leafless one” because before she was Aparna, she was born as Uma the princess. Before Uma was born on Earth, she was a nymph in the heavens. At that time, Lord Brahma (the creator) was happily married to his wife Saraswati (the goddess of learning), and Lord Vishnu (the preserver) was enjoying his wife Lakshmi (the goddess of wealth). Shiva, however, was a consummate bachelor, and lived alone. The other Gods went to him and told him that a wife would benefit his grumpiness, and his life, but Shiva rejected the notion, as he was content. So the Gods sent down the Mother Goddess Sati, to be born on Earth as Uma, to Queen Mena and the great mountain King Himavan (also father of the Goddess Ganga).

Uma’s destiny was to marry Lord Shiva, so as she grew up as a young girl she was fascinated with him, his life on the Himalayan mountains, and his ascetic life. When it came time for her to be married, her father wanted to hold a Swayamvara. This tradition allowed the princess to choose her husband from all of the eligible Princes in the land. They would all come in their best attire, stand in a line, be introduced one by one, and the Princess would walk from Prince to Prince, with a garland in her hand. When she found the one she liked, she would garland him, and they would be married. I probably would have picked the hottest one with the best kingdom.

I’ll bet that ancient tradition surprises many people and breaks free some of the misconceptions that Indian culture is all Patriarchal.

The thing about the Princess Uma however, was that she wanted to marry Shiva and declined the Swayamvara much to her father’s dismay. While he was not really on board with his beautiful princess daughter marrying a grumpy god who basically camped out in the mountains and lived a very simple lifestyle, he really couldn’t say no, he was a God after all. So Uma donned simple bark and leaves as clothing, and went to the forest to pray for Shiva to come down and marry her.

Shiva wasn’t impressed. First, as a God he knew all, so he knew that she had been sent to Earth to eventually become his wife. Second, he thought that she was a spoiled princess, so why would she really want to live his lifestyle. And third, I think he just wanted to be difficult.

Each day Uma walked all the way up the mountain, and decorated his simple dwelling with flowers and gifts of love with the hope that he would be charmed. But he never even looked her way.

Part of the reason that Shiva was so disinterested, was because his previous wife Sati (the very mother goddess that was reborn as Uma), had jumped into a sacrificial fire and killed herself after her father humiliated her in his court, because of her love for Shiva. So distraught was Shiva at the loss of his great love, that he decided to remain a bachelor for the rest of eternity.

Desperate, Uma brought in some reinforcements: The Goddesses Rati and Prithi (who represent lust and love) and Kama the God of Love. The three brought birds and bees, honey and fruits, and many sinful and joyful scents into Shiva’s abode. One day, in a fit of joy, Kama shot a love arrow into Shiva’s chest. And then, Shiva had enough.

He opened his third eye (the one thought to eventually destroy the world) and burnt Kama to ashes. Now there was no God of Love, and his wife, Rati, was unconsolable.

An aside here: There was no longer a God of Love, so love could cease to exist. To rectify this imbalance, Uma pledged that her first born son by Shiva would be Kama reborn. But she still had the problem of Shiva not noticing her…

So she decided to take it up a notch: She went to the forest and prayed there for a long time (hundreds of years). Her penance was so great, that fire erupted around her, rain poured down on her, insects crawled oer her skin, but she never lost her focus on Shiva. The other Gods were annoyed with Shiva, they thought, “enough is enough,” and went to him and told him to go down and marry her. Still irritated, Shiva declined again. So all of the Gods went down to bless her. Apparently, her focus was SO great that she didn’t even notice them all surrounding her. At that time, she didn’t eat anything, not even leaves, such was her devotion, so the Gods themselves became blessed by her penance, and named her “Aparna – the leafless one”.

At a certain point, Aparna’s penance became so great that it surpassed Shiva’s own. Her penance actually hit him with a force that pulled him out of his meditation. Finally, he was impressed. He came down and took her as his wife. And at that point, she became Parvati.

There are so many stories of Shiva and Parvati, who had a loving and volatile relationship. But now we will get back to the Name, which is the theme of this story. I promise to write more about the two lovebirds later not to mention some stories that highlight the strength and power of Parvati.

You can see how once I learned the story of my name, that I was even more proud of it. My Mom named me after a strong willed superwoman, and she often said to me while I was growing up that she named me appropriately. My sister’s name, Priya, means love. A bit more mellow, but apparently Priya was one of Uma’s best friends.

While my Montessori Preschool teacher (who was also a Nun) was very impressed with my name, there have been other times that my name was highlighted in a slightly embarrassing way:

Every time we had a substitute teacher or the first day of school with any teacher: They would call roll, “John Right, Kim Smith,” PAUSE. Everyone would giggle and point at me. “It’s her…” And I would say, “My name is Aparna and my last name, Sreenivasan, is phonetic.” I’m sure the first few times it didn’t bother me, but after 12 years of public school, it got old. Of course, my French teacher in High School used to say my name with the most beautiful rolled r’s and accent. That was very pleasant.

But in 50 years, people stumbling over my name, or pronouncing it incorrectly even after I told them how to say it, never really bothered me. It didn’t even bother me when the kids on the playground in 4th grade turned my name into “Apenis Spermasvasan”. Clever, and plus they were doing that to each other, even Smith could be turned into a dirty name. So, these instances were just was the way it was. Until two months ago...

I was in a place of business in Pacific Grove with my son. I had purchased something for him online and needed to pick it up. When we walked in the door a fifty something blond woman walked up to us. I introduced myself and said that I was here to pick up our online purchase and that I had called ahead earlier to make sure it was there. She looked at me and said, “Oh yes, you are the one with the name.” I was confused, “the name?” I asked. “Yes, that name that I can’t even say that is so long.” As we walked into her office she sat down at the computer and said again, “Ugh, how do I even spell it to find it?” I said, “Well the last name is phonetic,” and spelled it for her. “What kind of name is that anyway?” she responded. At that point I just politely asked for a refund for my purchase and we left.

When I told my husband about the incident, he said that his response would have been, “Well, why don’t you google Aparna Sreenivasan, and you will find a bunch of people that are doctors and PhDs…” I told him that’s not my style. But it was cute that he wanted to protect me somehow from this woman’s stupidity. Kind of like the time a bike shop owner made me cry when I accidentally made one of his bikes tip over in the shop. I came home crying, and my husband (at that time boyfriend) rode over to the shop and told off the owner for treating me poorly. It’s always nice to know that someone has your back (of course, when he told off the bike shop owner he was only 27 and now as a 50 something, he would never do something so brash, unless someone hurt his kids, then all bets are off).

The incident with the woman brought on many questions: Did she not like me because I was brown? Was she irritated because I was wearing a mask and she wasn’t? Did she think I didn’t belong here? Did she not like my son’s haircut – he had just gotten some fancy new haircut that afternoon…Should I have told her that I am named after an amazing badass goddess who would kick her ass? Hmmm…I guess I was triggered…

Names are an important part of my job, and life. I am a professor, so every semester I learn so many new names. I make it a point to ask my students how to correctly pronounce their names. And I often make connections with my student’s personalities and their names.

So what is in a name? Does it define a person? Does it have meaning? Should we respect names as we respect individuals? Over a lifetime it seems as though a name does begin to define you. It is so much a part of who you are. And many names, like mine, have deep familial, historical, and cultural value. I decided to write this story because of the incident with the woman in the local store, but while the idea began with that, you can see that the story took on many directions and now I’m left with so many questions. But I do have one clear answer: I have a deep love for my name that my Mother chose for me and so suits me because I too, like the Goddess, can be stubborn, strong, and at times, a badass. Did my name help define those aspects of my personality? Or was it just meant to be?